ALL THINGS MOTORING INTERNATIONAL would like to acknowledge that this article is extracted from the incredible magazine - Motor Sport we extend our appreciation to Mike Doodson and Martin Harrison for this excellent article to celebrate Nelson's birthday.

Let’s admit it from the start.

I like and admire Nelson Piquet. It can be a trying experience, though, to be unmasked as a Piquet supporter, so let’s remind ourselves of his extraordinary talent. He left Brazil for Italy in 1977 at the age of 24, won races in the European F3 championship while living in his truck, then moved to England to contest the (two) British titles in 1978. Before the season was half complete, he found himself in Formula 1, vaulting any intermediate category, and subsequently went on to win 23 GPs and three world championships. Intelligent, incisive and no sufferer of fools, he commanded deep loyalties that remain firm to this day.

Yet the negative aspects of Nelson that critics hold against him, occasionally in these pages, require someone to defend him, even though he’s never sought to do so himself. The supposed blots on his character would have to include suspicions about the legality of several cars he drove, doubts about his commitment to the job with the two F1 teams (Lotus and Benetton) that employed him at the end of his career, and a long list of scurrilous and personal insinuations he slung at rivals. Not least among his targets stand the saintly figures of Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell.

There is scant chance of Nelson, with his gruff contempt for self-appointed moralisers, ever achieving that sort of holiness, although he is an expert at knocking haloes askew. Throughout our most recent meeting, this summer just past, my old friend was wonderfully relaxed, if a little haggard at almost 61 years old. I was treated to the familiar torrent of comic abuse, delivered in all directions in his staccato and gloriously scatological style.

To get the full flavour of Nelson, it is essential to puncture the widely held myth of his ‘laziness’ and to demonstrate just how dedicated he was to making his way in the sport, even if it flagged briefly at the end. This is a man who built his first single-seater (a Super Vee) virtually single-handed, from the ground up. Yet such was his confidence in his own abilities, when he left Brazil for Europe, that the deals he had done with sponsors at home were based solely on outright wins, a scheme that would net £4000. “Here in England we did the same with BP and Champion: only to get money for winning. Instead of just a little bit of money for carrying the stickers, I got £600 from each of them for every win. And I won 14 races…”

Piquet beat Derek Warwick to 1978 F3 championship in his Ralt RT1

Motorsport Images

The British F3 campaign, in which he beat Derek Warwick by a handy margin in the BP championship, attracted attention not only through Nelson’s successes, but also for his dedication to testing. Those cash bonuses allowed him to run a test car, with which he covered twice as many miles as he would do in the whole season’s racing, and he spent as much time under the car as in it. Rather than use the Toyota-Novamotor engines supplied from the UK agent’s pool, he was also in the habit of delivering his own units to the factory in Novara, which is a long haul in a clapped-out Cortina estate. He would take a couple of litres of British fuel, too, to ensure a perfect tune on the Italian dyno. Nelson had learned that being minutely prepared in advance was the best way to avoid having to take risks in races. While this was a policy that would serve him equally well on the Grand Prix circuits, it has also led to ill-advised accusations about his level of commitment as a driver.

Nelson had the knack of finding good men to support him. Managing the F3 campaign for him in England was Greg ‘PeeWee’ Siddle, a tall Australian whom he had met at the Ralt factory, where he had rented workshop space from Ron Tauranac in 1978. Siddle was drawn by the Brazilian’s astuteness (they are devoted friends to this day) and ability to think on his feet. He nominates a victory at Cadwell Park in June as the best race they did together in F3, largely because Nelson perceived that the wet track was drying fast and chose to start on slicks, dropping almost to the back of the field before conditions improved. With his hunch vindicated, he surged past the likes of Tiff Needell, Stefan Johansson and Warwick to grab victory. Rather typically, Nelson believes that his best race in F3 was an outwardly routine all-the-way victory at Snetterton. The reason:

“I did 20 laps, all within a tenth.” Technique over heroics. The die was cast for his future as a Grand Prix great.

First to call from the F1 world was Ensign boss Mo Nunn, who offered his car to Nelson for the German GP. Starting 22nd, the rookie made a stupendous getaway, only to retire when his DFV (which he had inadvertently buzzed in qualifying) failed just after half-distance. For the next three GPs Nelson was recruited to drive Bob Sparshott’s ageing McLaren M23, with a best result, at Monza, of an unlapped ninth. Sparshott was sufficiently impressed to offer a contract for 1978, and Nelson was keen to sign it, but PeeWee, sensing that there might be a more attractive option, engaged his friend in what he now calls a “robust discussion” about the Sparshott deal on the way home after Monza.

Piquet at Monaco in 1983

Motorsport Images

Nelson now claims that Larry Perkins, a former Brabham driver, had already advised him not to sign anything until he’d discussed it with his old boss Bernie Ecclestone. Piquet, straight-faced, maintains that he had no idea at the time who Bernie was. PeeWee, though, recalls things differently. “I always felt there was more to be had than the Sparshott offer,” he says, “so I suggested we rang Frank Williams. I’d already had a conversation with Bernie, who had come all the way down the pitlane at Monza for a chat, and it was he who advised us not to sign anything without talking to him first.

“What happened then was that Nelson went to see Frank Williams, but only a couple of days later he got a call from Bernie, who had somehow got wind of the meeting with Frank. The upshot was that in Canada, for the final GP of the year, Nelson was racing a third works Brabham-Alfa.” He qualified respectably and finished the race a lapped 12th, hampered by a broken exhaust and the loss of two gears.

It was enough to guarantee a permanent place as John Watson’s replacement for 1979.

While popular lore records that Ecclestone took advantage of his new driver’s lack of business acumen to impose harsh conditions, Nelson insists that he never felt exploited by his new boss. “Bernie came with the contract and said, ‘Can you understand English?’ I said yes, so he made me sign a paragraph stating I had read the contract and understood it. After I signed it, he said, ‘Don’t you want to know how much I’m going to pay you? I’ll pay you $50,000 for the next three years, and 30 per cent of the prize money.’ That was fantastic. I was in Formula 1! I didn’t care about the money, all I ever wanted was to be in Formula 1. And I had signed a contract.

“I was very happy with it. In the first year I made close to $800,000, because I won the [BMW] Procar series, there was a lot of money for racing those cars. Then, every time I found a sponsor in Brazil and gave the cheque to Bernie, he put it in the bank and gave back half to me. We had some big companies, domestic appliances, beer, stuff like that, and they paid $80,000, sometimes $200,000.”

At Brabham, Nelson would find himself working alongside Gordon Murray, the fast-rising South African engineer whose left-field genius has provided F1 with some of its cleverest, most stunningly attractive designs. “Nelson was bloody clever, in ways of setting up the car and driving it,” PeeWee says. “At the time he went to Brabham he was already working on things like a cockpit-operated brake-balance adjuster for his F3 car, and that was a godsend to Gordon because Niki Lauda wasn’t interested. ‘It’s just one more thing to break,’ he said, but Nelson pushed ahead, insisting to Niki that Gordon was the right guy to make sure the clever bits would not break.”

The partnership with Murray didn’t fully blossom until 1980, by which time Ecclestone had finally been persuaded to ditch the disastrous engine deal with Alfa Romeo and return to Cosworth power. Murray’s nifty Brabham-Ford BT49 was blessed with such effective aerodynamics that the only circuit where it would need even a smidgen of front wing to perfect its balance was Monaco.

It would give Nelson a maiden F1 victory, at Long Beach, with only two other cars finishing on the same lap. On the way to setting pole, a delighted Nelson noted that all four Goodyears blistered at exactly the same moment.

By now he was part of Brabham’s devilishly ingenious band of British and Commonwealth mechanics, led by Murray, whose respect for the fine print of the rules tended to go AWOL whenever an opportunity arose to defeat them. In the years to come there would be reports of lightweight qualifying cars that were craftily ballasted before officials could get them to the weighbridge. There were lead-reinforced nose-cones, special (40kg) seats, even heavyweight wheels, and I can remember Murray doing a poor job of denying that he’d built a lightweight qualifying car. Of course, the Brabham gang was not alone in these unsporting subterfuges, but nobody else was in the same class.

“Niki gave me horizons in other directions. They good for me”

In 1979, when Niki Lauda was his team-mate, Nelson wasn’t averse to such shenanigans in his search for an advantage over the Austrian. “At Silverstone, the car was 18 kilos overweight, and before qualifying I got the mechanics to take out first gear, because I didn’t need it for a flying lap. I got them to take out the fire extinguisher, too, which put my car just on the minimum weight. But Niki saw the car on the scales and went to complain to Bernie; he wanted to know why his car was 15 kilos heavier than mine. After that, my mechanic was taken off the job and I was not allowed to visit the Brabham factory any more, because Niki realised I was spending my days there doing these things.”

Far from souring the relationship with Lauda, the incident cemented a great and enduring friendship. “What I learned with Niki was how to communicate with the team,” he says. “Before I drove for Brabham, I never ran with any engineer. I had my own car and I made all my decisions about the set-up, I just told the mechanic what to do. Niki could describe what the car was doing, whether it was rolling or understeering or oversteering. I tried to feel the same things to tell the engineers.

“That was a good thing I learned. But the most important thing was that when I came into the team, Niki never left me by myself. He would take me with him to the restaurant at night, and I don’t think today there is any relationship between team-mates like that. Usually when drivers are new in the team, no one wants anything to do with them. But Niki was so helpful on this point. He also gave me horizons in other directions. We started to talk about flying, he helped me to understand about aeroplanes, he convinced me to buy a plane, he told me what to do. All these things I got from Niki were very good for me.”

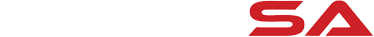

Mansell, Williams and Piquet in 1986

Motorsport Images

Riccardo Patrese, who joined Brabham in 1982, earns rather fewer points from Nelson as a valued team-mate. “Well, he was a crying boy,” Nelson says. “He was always complaining about the car, saying that BMW would not give him equal treatment. But he was just plain bloody hard on the car. There was no way he could drive on the limit for 70 laps: the gearbox and driveshafts would not take it. If you are in front you have to take care of the car. How many drivers get in front and blow the engine or the gearbox like he did, or just crash out as he did when he was leading at Imola in 1983? Only the useless ones…”

This is the abusive stance Nelson adopted towards some of his toughest rivals and it has kept certain journalists’ self-righteous rebukes tumbling down on him ever since. For Alain Prost, however, he has always had admiration. In the lead-up to his 1983 title showdown with the Frenchman, Nelson frustrated the media’s plans to beat it up into a personal grudge-fight by inviting ‘the Professor’ to have lunch with him on his yacht in Monaco, ensuring that there were photographers there to record the meeting. Then, after Prost had retired from the deciding race at Kyalami, Nelson spoke out in his rival’s defence. “It was not Prost who lost the championship,” he told a bunch of French reporters post-race, “it was Renault who threw it away.”

Not that Prost escapes unharmed from Piquet’s uncompromising wrath. In particular, he spoke out bitterly against his rival’s behaviour at Adelaide in 1989, when the circuit’s virtually non-existent drainage failed to cope with a pre-race monsoon. Following some worrying incidents on the puddles during a special set-up session, several leading drivers, among them Prost, solemnly told TV commentator Barry Sheene that they intended to boycott the race. “Usually I never say anything bad about Prost, because I like him,” Nelson told me at the time. “But he was the one who screwed us completely at Adelaide. We were a very strong group: we had six or seven drivers who said, ‘We will not start this race.’ But Prost turned around, without saying anything, went to his car and sat in it. After that, everybody was dead, everybody went to their cars. Then he did one lap and stopped. Why? Because he had already won the championship and had nothing to prove. That was very brave of him…”

That is an over-simplification of the alarming events in Adelaide, because the race was actually red-flagged after two laps and Prost didn’t so much quit as decline to take the restart. But Nelson’s assessment is still valid, because his worst fears were confirmed when both he and Ayrton Senna, blinded by the spray, escaped serious injury by inches in separate collisions. Piquet hit Piercarlo Ghinzani’s Osella in the watery gloom and he was lucky to get away with nothing worse than concussion.

Honda followed Piquet from Williams to Lotus, but the partnership produced few results of note in 1988-89

Motorsport Images

It is the toxic rivalry with Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell that is most clearly recalled by Nelson’s detractors, and so great was the conflict with his countryman back home in Brazil that it commanded the headlines and even the makings of a bitter court case. Although the two men had been trading disobliging remarks ever since Senna’s debut season in 1984, TV Globo’s veteran reporter Carlos Galvão Bueno says that the antagonism was essentially light-hearted, at least until 1986. Throughout that season Senna had been accompanied to most of the races by a younger fair-haired man known to all as ‘Junior,’ whose only official function appeared to be helmet guardian. In the off-season a reporter from the Jornal do Brasil informed Nelson (who has always deliberately avoided reading newspapers) of some comments about him that Senna had made in print.

Senna had probably only been teasing, but Piquet, for whatever reason, responded with a barbed insult (“Just ask him why he doesn’t like women”) that instantly found its way on to front pages across the country. “Then Senna’s manager tried to bring a legal case against me, in the courts, claiming that what I had said was a lie,” Nelson recalls. “Everybody published that story, but that was the only phrase I had ever said against him in public.”

“It is the toxic rivalry with Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell that is most clearly recalled by Nelson’s detractors”

To protect himself, Nelson also engaged a lawyer, who would earn his fee in the course of some careful digging through court documents. Rather than going into all the prurient details here, I’ll simply report Nelson’s assertion of the lawyer’s discovery that Senna’s brief 1981 marriage to the teenage Liliane Vasconcelos had not ended with a straight divorce, but rather in an annulment. Perhaps unfortunately for Senna, by then his own legal people had noisily served a writ on Nelson, personally, at the 1987 Brazilian GP in Rio. An indignant Nelson subsequently had a shouting match with Senna’s lawyer about the results of the ‘dig’, whereupon the legal case was abruptly withdrawn and Senna’s attorneys turned conciliatory, to the extent of quietly settling the opposite side’s legal expenses. Brazilian colleagues have confirmed to me that the matter never got as far as a courtroom.

Galvão Bueno, always a close and trusted friend of Senna and the family, is a respected journalist with his nose close to the ground. He was therefore well aware that Junior’s presence so close to Ayrton, and perhaps the fact that they sometimes shared a bedroom, had raised questions about the driver’s sexual orientation. “I know Piquet claims that I suggested to the family to ‘get rid’ of Junior,” he told me recently, “but it’s not true. What I can say, though, is that I advised them to be careful.”

Piquet scored the second of his three Benetton victories at Adelaide in 1990

Motorsport Images

Today, of course, the sexuality of anyone in the public eye is of little concern to most of us, but that was not the case 30 years ago, and even less so in Brazil’s often intolerant, macho environment. While it is easy to condemn Piquet’s remark to the journalist as ugly and prejudiced, Senna in turn seems to have been desperately anxious to dispel any doubts about his sexual orientation. It became known that he had contracted an attractive female model to accompany him to some races and sponsorship appearances. Later, the Brazilian press drew attention to numerous other outings where he was photographed arm-in-arm with female celebrities who weren’t seen with him again.

For what it’s worth, the evidence that has emerged suggests that Senna, though cautious about making friends from the racing world, nevertheless formed close and sometimes intimate relationships with people, male and female, who were not involved in the sport. Despite strong evidence to support this supposition, it is emblematic of the loyalty he inspired that in the 20 years since his death only one or two of the people with whom he was involved have sought to benefit materially from their intimacy with him by talking to the press.

The unpleasantness between Piquet and Nigel Mansell was all the more acute because it was a fight between team-mates. In August 1985, when Nelson signed with Frank Williams (for a then-record $3.3 million), he claims he had been promised number one status. Mansell didn’t have much in the way of star quality at the time, but by the end of the season his innate ability was coming into bloom as he won back-to-back GPs at Brands Hatch and Kyalami. Nelson cannily anticipated the game-changing consequences this would have for him at Williams. So, in order to steal back some support within the team, he deliberately set out to pick a fight with the Englishman, thus forcing a division of loyalties.

Although Nelson had a handsome win in his first outing with Williams-Honda, in Rio, the team had been weakened by the car accident that so grievously injured Frank only a few days earlier. Nelson’s driving also seemed to have lost some of its consistency: by season’s end he had won four races to Mansell’s five and also suffered a number of untypical retirements, albeit not as many as those so carelessly racked up by Mansell. The now-celebrated climax to the season at Adelaide, where the two Williams boys in their Honda-powered FW11s were in contention for the title, ended when a tyre failure eliminated Mansell, and Piquet was forced to stop for fresh rubber after he felt one of his own Goodyears about to fail. Prost took the crown, a turn of events Nelson emphasises would not have occurred if Frank Williams had been in a position to deliver on the verbal promise of number one status that he’d made when their contract was signed.

Piquet leads Mansell during their ’87 Silverstone battle

Motorsport Images

At Imola in 1987, during qualifying, another tyre failure sent Nelson crashing at Tamburello. Still concussed, he was back two weeks later for the Belgian GP, well under par. “That was bad,” he admits. “I had lost 80 per cent of my depth of vision, and I only told anyone at the end of the year. Otherwise, they would not have let me race. That’s the reason why I was so bloody slow!” Did Mansell ever try to take advantage of his lack of sharpness? “He didn’t know! Nobody knew! In the first race after Imola I was one and a half seconds a lap slower, and I somehow managed to hide it.”

At Silverstone in July Nelson suffered defeat at the hands of ‘Our Nige,’ who had made an early and unexpected tyre stop after a wheel balance weight came off. Mansell fought back, memorably tracking down his team-mate and selling him what appeared to be a crafty dummy at Stowe to snatch the lead with three laps to go. Unknown to the public and TV commentators, however, Nelson was paying close attention to his fuel read-out, which was showing a worryingly negative figure. Knowing that his team-mate’s fuel management skills were consistently inferior to his, Nelson was confident that Mansell’s tanks would run dry before the flag appeared. What he didn’t know was that the Honda engineers had made an untypical pre-race miscalculation. “Mansell was a long way under on the fuel, so he took a chance. He knew he was going to run out of fuel, and he did … 400 metres after the line.”

The Briton’s victory that day, which owed as much to Honda’s mistake as his own derring-do, is held up as one of his greatest. I’ll leave readers to make their own judgment on that. Not that Nelson has ever shown any resentment about having come so close to securing what would have been a sensational win. “I was doing my job, exactly, using the power only when I could, and so on. I didn’t push harder, because I knew how stupid it would look if I ran out of fuel. He gambled, he won.”

“Mansell was a long way under on the fuel. He gambled, he won”

Three victories for Nelson in late-season races, two of them at the expense of the luckless Mansell, would clinch his third title. The most satisfying of the trio was at Monza, where he was allowed to use the active suspension system he had been testing exhaustively for more than a year. Mansell, who had bad memories of a similar computer-controlled system that had failed under him when he was a Lotus driver, had refused to take part in most of the ‘active’ testing and had to make do with conventional springs. His feelings can only be imagined as the ‘active’ car and its tyre-sparing limousine ride carried the Brazilian to a seemingly effortless win.

Despite the Imola concussion and Mansell’s six inspired wins throughout the 1987 season, Nelson had employed his innate sensitivity to exploit the speed of the all-conquering Williams-Honda without stepping over its mechanical limits as boldly as his English team-mate was inclined to do. His three wins might appear to naysayers as something less than inspiring, but then he also picked up seven second places.

How differently things might have turned out if only Nigel hadn’t picked the silly fight with Senna that knocked him off the road in Belgium, or hadn’t hurt himself in Japan in a completely unnecessary qualifying crash that eliminated him from the last two GPs of the season… in both of which his team-mate was destined not to finish.

Piquet made his first Brabham appearance at Montreal ’78

Motorsport Images

The poisonous atmosphere at Williams had taken all the fun out of racing for Nelson, and he started to enquire about openings elsewhere. But rumours were circulating that Honda, whose management was inclined to blame the loss of the 1986 title on Frank’s infirmity, might bring its contract with Williams to an early end.

Because Honda also placed a high value on the Brazilian, Nelson knew that Williams stood an even higher chance of losing Honda if he departed. His response was admirable.

“When I heard that if I left Williams there was a chance that they would lose the engine, I told Patrick Head, ‘It’s OK, I [will] put up with the shit and will stay, because I don’t want to be the reason for you losing the engine’. Patrick believed that Williams had the Honda engine for sure in 1988, it was not important what I did. So I went straight off to talk to Lotus.”

One month after the news of Nelson’s Lotus deal had been released in Hungary, Honda casually offered its “thanks” to Williams for its help and announced that it would be supplying only Lotus and McLaren in 1988.

Frank and Patrick, now without both Piquet and Honda, were left in the cold with a race-winning car that had a big empty space behind the cockpit. “As I have pointed out [many times],” Nelson says, “we should have won [the title] in 1986, that first year with Williams, and if I had continued with Williams and with Honda, we could have won four years in a row, no problem.”

Nelson would race on in F1 for another four years. His two seasons with Lotus in 1988/89 were financially rewarding but a sporting disaster: he says the car was so seriously lacking in torsional stiffness that it wasn’t worth even attempting to sort it out. For the final two years, at Benetton, he had to accept the payment-on-results scheme offered by Flavio Briatore. Two wins in 1990, in Japan and Australia, paid off handsomely, to be followed in 1991 by a famous ogre-slaying in Montréal. Mansell, who had a comfortable victory in hand with less than a lap to go, somehow managed to stall his Williams’s Renault V10 while waving to the fans at the hairpin and stuttered to a stop within sight of the flag.

The farewell to F1 was not the end of Piquet the racing driver. He had two attempts at the Indy 500, sorely injuring his feet in a heavy crash while practising for the first, in 1992. “I’d retired from full-time racing, but there were two things I still wanted to do, Indianapolis and Le Mans. At Indianapolis, they also paid me a lot of money. Actually, the car [a Lola-Buick] was very easy to drive, it was flat everywhere. Everything there is aerodynamics – and the stagger of the tyres. I really loved the place.

Piquet is reunited with his 1981 championship winning Brabham BT49C

Motorsport Images

“The problem is that when you’re testing there, every 16 laps you have to stop and come into the pits to refuel. If you lose just 20 minutes, you have to start all over again, because with the temperature changes and all the aerodynamics, everything is very sensitive when you’re doing 400kph.

“So I was very frustrated when they showed a yellow [flag]. I calculated very quickly that if I could get in, I could stop and still do one run. I was in Turn 4 when I lifted off, to be able to go into the pits, and when I lifted I went off. The hit was very hard.”

So hard, in fact, that the resulting leg injuries left his surgeons contemplating amputation. After several painful interventions, he went home with his feet intact, but not as useful to him as they had been. Walking downstairs is now a serious trial for him. But still he persevered with his non-F1 ambitions: he was back at Indy in 1993, only to have an engine failure, and was equally luckless in two outings at Le Mans that gave him just four hours at the wheel. He initiated a category of sports car racing in Brazil, took part in the Nürburgring 24 Hours and finally knocked his career on the head at Interlagos in 2006, sharing an Aston Martin DBR9 with three other drivers, one of whom was his son Nelson Ângelo Piquet.

He lives happily in Brasilia, where he runs Autotrac, the hugely successful satellite tracking company he set up after seeing a truck fitted with a similar system in the US back in 1992. The days of relentless womanising are long behind him now and he has been happily married since 1998 to Viviane de Souza Leão, whose two sons with him have brought the Piquet brood up to seven. Watch out for 15-year-old Pedro (“I think he is the best of all my boys”), who is already a consistent winner in European karting.

For all the extremes of affection and hostility that Nelson Piquet attracted during 14 years in the F1 spotlight, he is left with no regrets. “I didn’t go racing in Europe for glory or to make a big name for myself,” he once told me: “I came because a couple of friends thought it was a good idea, and they found the sponsorship for me to do a season of Formula 3. I would have been quite happy to go home at the end of 1977 with a bit of Italian and some nice memories. But it all worked out differently…”

Our thanks to Martin Harrison of BMW UK for his help with this feature.

ALL THINGS MOTORING INTERNATIONAL would like to acknowledge that this article is extracted from the incredible magazine - Motor Sport we extend our appreciation to Mike Doodson and Martin Harrison for this excellent article to celebrate Nelson's birthday.